Written by Erin Plum

The phone finally rang while my husband and I sat in our car in a Jiffy Lube parking lot in a seedy part of town. We had been waiting for this call all day and had been doing our best to keep busy—thus the oil change on a Wednesday afternoon with our two young kids buckled into their car seats behind us. We had been prepared for the worst—the ultrasound had never looked good. But there was no use getting upset until we knew anything for sure.

Over the past eight years, my husband and I had weathered plenty of storms together including the harsh realities of his medical school and residency, the loss of family and friends to suicide and car accidents, financial hardship, and incredible stress from both of our jobs. I worked in a large, inner city hospital as a nurse where I saw horrific traumas and abuse daily. In the surgical recovery room, children cried out in pain and fear and it was my job to stay calm.

I had given birth to two children—one emergently and the other while dealing with postpartum anxiety that would keep my heart racing at night. Ten days after our second child was born my husband started his first year of residency, working 80-100 hours a week. I became accustomed to handling the care of our infant and toddler, home and car maintenance, yard work, appointments, and keeping our social calendar while working part time. I learned to keep my emotions in check—holding it together even when I felt like I was crumbling. I had become a strong, resilient person—capable of handling stress and disappointment.

The radiologist who broke the news was kind and patient and answered our questions. She told us that I had triple negative invasive ductal carcinoma—an aggressive cancer that can be resistant to treatment and tends to recur. We asked questions. We wrote things down. We made a plan for next steps. I felt tears welling in my eyes, but I looked out the window and started formulating a plan for how we were going to tackle this next hurdle.

We received the news in May, just four weeks away from moving to New York City to complete the next three years of my husband’s training. We were leaving behind our parents, siblings, and many friends. Our entire support network was now going to be in another state. Our house in Baltimore, Maryland had been on the market since March and was now under contract. I had kept it spotlessly clean for weeks and left with our two-year-old daughter and baby son any time someone wanted to come by to see it. Now, in the midst of all the packing and preparations for our move, I needed immediate scans, blood work, second opinions, and surgery scheduled to place my port for chemo.

As the reality set in over the next days and weeks, the tears began to come. I cried and packed our house. I cried and held my babies. I cried and scheduled appointments. I cried in bed in my husband’s arms at night. I felt overwhelmed by my own life—my head spinning with details and statistics and emotions—trying to make sense of my new reality. This wasn’t me. I didn’t fall apart. I didn’t cry for days. I didn’t feel bowled over by helplessness and fear.

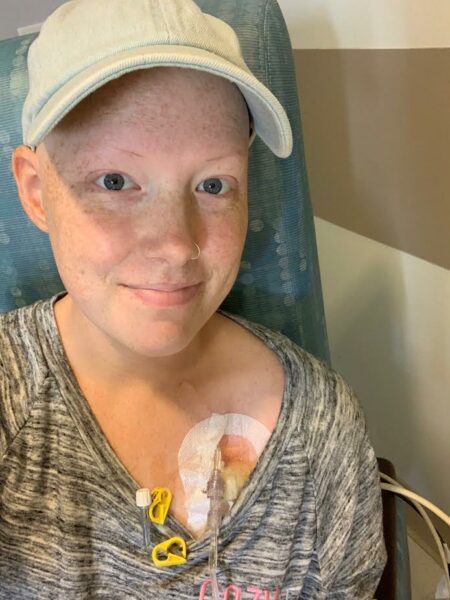

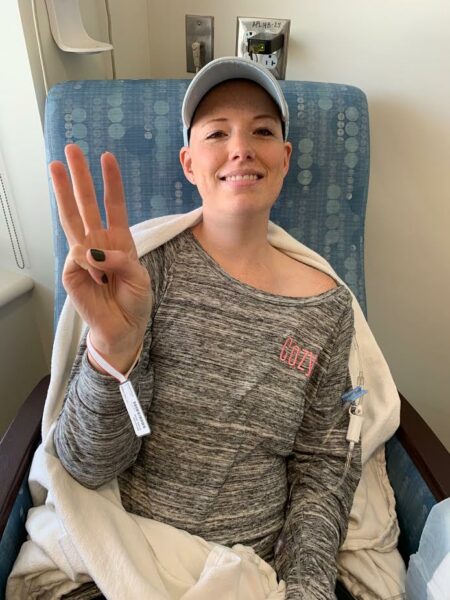

I had my port placed four days after we moved to New York and started chemotherapy two days later. Life was happening so fast I could barely keep up to process all the change and hurt that I was feeling. With the start of Adriamycin and Cytoxan, I began dealing with severe mental irritability and sensory overload. I couldn’t tolerate loud sounds, heat, crowded places, or even the crying of my kids without feeling like my brain was going to explode.

As I lost my hair and then my eyebrows and eyelashes, I barely recognized myself in the mirror. Who was this person who couldn’t keep up, cried at the drop of a hat, and was filled with anger and fear about almost everything? I sank into a deep depression and found myself spending a lot of time shut in my bedroom, staring out the window and wondering what had happened to me and my life. Why did I get cancer? Why now? Why me? What if I die? Will I ever feel happy again?

In desperation, I began to write about my thoughts and feelings about having cancer and all the ways it was affecting my life. I wrote out the anger and fear and sadness and hurt. I processed the hard questions even if I didn’t come up with answers. I sat in my feelings for weeks and months, giving myself space and time to acknowledge all that my heart and mind were going through. I cried and raged and felt all of the feelings that were so overwhelming to me. I felt my weakness—both mentally and physically.

As time went on, I began to see that my feelings were pointing to all that my body was going through and that those feelings were worthy of being respected and validated. As I started leaning into my grief, I started to heal. I began to feel peace and acceptance in my heart—not because I had answers—but because I was going through the lowest, weakest time in my life and still hanging on in spite of it.

Prior to cancer, I thought being strong meant I had to be unbreakable. I thought strength was holding it together and keeping my emotions in check. But I’ve begun to learn that by leaning into my weakness and validating all the emotions of grief and loss, I’ve become stronger than I ever was before. Being strong doesn’t mean I won’t break. Being strong means I’m willing to be broken in order to heal.